This webpage won't be updated anylonger.

Please visit: www.gerhardsengerner.com

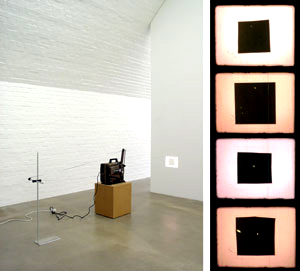

Jonathan Monk, Square Circles Squares, 2002, 16mm

film projection

Sol LeWitt, Irregular Grid, 2001, goache on paper

#009722, 152 x 152 cm

Peter Friedl, Untitled (Berlin), 1998/2003, wall

painting

Peter Geschwind, Sound Cut, 2002, DVD video/audio

Liam Gillick, Doubled Resistance Platform #2, 2001,

powder coated aluminium and transparent plexiglass

Ceal Floyer, ...again and..., 2002, ballpoint pen

on paper, 29.7 x 21 cm

Michel Majerus, Untitled, 2001-2002, 9 paintings,

acrylic on canvas, each 60 x 60 cm

Peter Friedl, Untitled (Berlin), 1998/2003, wall

painting

Peter Geschwind, Sound Cut, 2002, DVD video/audio

Liam Gillick, Doubled Resistance Platform #2, 2001,

powder coated aluminium and transparent plexiglass

Liam Gillick, Doubled Resistance Platform #2, 2001,

powder coated aluminium and transparent plexiglass

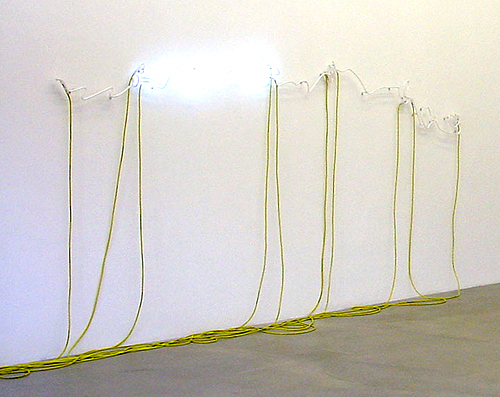

Rirkrit Tiravanija, Untitled, 2003, neon tubes,

electrical cables power supply and control unit, approx 50 x 400 cm

Rirkrit Tiravanija, Untitled, 2003, neon tubes,

electrical cables power supply and control unit, approx 50 x 400 cm

Pressrelease

Perfect Timeless Repetition

Duration: Jan 17–Feb 28, 2003

Opening: Jan 17, 19.00–21.00

We are delighted to present the group show "Perfect Timeless Repetition".

This ambiguous

theme features a range of different work by Ceal Floyer, Peter Friedl, Peter

Geschwind, Liam

Gillick, Sol LeWitt, Michel Majerus, Jonathan Monk and Rirkrit Tiravanija.

The title of the show is a quotation from Glamorama (1998) by Bret Easton

Ellis.

Ellis' practice of extreme inter-referentiality within his own stories, and

shrewd appropriation

of real identities for the characters of the extras in Glamorama, may be seen

parallel to the

ideas and art work by Liam Gillick (b. 1964). Gillick draws upon vast numbers

of references

in his work as he experiments with the notions of time, politics and situations

that could have

coincided or that may coincide. His writings, videos and filmatic collaborations

(with, among

others, Rirkrit Tiravanija) should be regarded as guidelines to his installations.

Gillick

presents a platform hanging from the ceiling occupying a corner in the gallery

space where

you turn around after you have passed through the whole exhibition.

In the same way that Bret Easton Ellis scrambles through people and popular

culture, the art of Michel Majerus (b. 1967, d. 2002) reflects our time and

the mass media. His cunning use of puns and slogans and overflowing imagery,

combined with often nihilist or apocalyptic

titles, leave us with an ambiguous feeling about life. We have included a

selection of nine

paintings by Majerus. He freely grabbed images and references from popular

culture and art history. In addition to the use of advanced computer programs,

he would daringly combine

elements of abstraction with figuration, and thick layers of paint with loose

strokes of

sketching. Often incorporating design and computer graphics, he produced vinyl

stickers and silk-screens in order to be able to perfectly mass-produce series

of images in variations. He aggressively questioned the notion of signature-style

and aesthetics, and these smaller works are excellent examples of his diverse

production.

Following the idea of popular culture we find the work by Peter Geschwind

(b. 1966). The

sheer speed of his looped DVD video "Sound Cut", 2002, recalls music

videos on MTV and

the audio instantly resembles the music of experimental electronica musicians

such as

Squarepusher or Aphex Twin. But this is actually a more detached and analytical

piece, while

still very much in the tradition of experimental music and music video. Geschwind

has used a

song by the band Dead Kennedys as an underlying structure for which he has

edited a video

consisting of video clips, including sound, of activities like dishwashing

and flushing a toilet.

When removing the original acoustics, he was left with the video clips that

very strictly

correspond to the elements of the song, and still keep a sort of melody. His

project can be

seen in relation to the music videos by the French director Michel Gondry

for Daft Punk's

"Around the World" (1997) and Chemical Brothers' "Star Guitar"

(2001). But Geschwind does

not just add pictures to a piece of music; by setting the parameters for the

editing of the video

according to the music [1], he followed the scheme mechanically in order to

combine the clips

- only to then remove the soundtrack and leave us with the sounds from the

clips.

"Perfect Timeless Repetition" could indeed have been an instruction

for a conceptual work by

the influential artist Sol LeWitt (b. 1928). His art and writings since the

60's have been crucial

to the discussion on art and art theory, and he still remains one of the most

active artists

today. A piece by LeWitt can have an instruction from the artist that should

be interpreted by

his assistants who produce the work. He often produces series with all possible

variations of

a theme. This way the artist is detached from dealing with certain aesthetics

and details as

his involvement is purely cerebral and conceptual. This attitude to production,

and his

profound ideas about art, only opens up to endless possibilities for realization

of art. It is a

pleasure to present a large gauche drawing on paper by LeWitt for this exhibition.

The notion of time is a definite understanding of the show's theme and occurs

in several of

the pieces by the artists featured in the show. Peter Friedl (b. 1960) is

a politically engaged

artist; context and history are evident parameters in his work "Untitled

(Berlin)", 1998/2003.

The artist has simply flipped the number "68" upside down. But the

slight disruption of the

typography gives it away and we realize the double meaning of the piece. In

the immediate

context of Berlin these numbers obviously refer to the student revolts in

1968, and the fall of

the Berlin Wall in 1989.

Ceal Floyer (b. 1968) presents a thoughtful text piece for the exhibition

where she has

written the words "again and" repeatedly on top of itself with a

ballpoint pen until it has been

completely blurred and unreadable. It is as if she tried to mimic her own

handwriting. The

writing has been carried out until it destroyed itself and mean nothing anymore.

Her ideas

always come through very strong because of the efficient means of execution

and her clever

use of references and comments, as well as an often amusing or ironic twist.

By placing her

piece in between LeWitt's drawing of repeated lines on top of each other,

and Friedl's

contemplation on history, her work underlines both the process of drawing

as well as the

notion of time.

Rirkrit Tiravanija (b. 1961) presents a spectacular piece consisting of five

separate neon

elements that light up in an endless rapid succession. The piece is a blow-up

from his young

nephew's attempt to imitate his handwriting. The scroll illustrates an illiterate

child's difficulty

understanding the complexities of symbols and letters. We might not be able

to read his

words, but the lines and the curls are as beautiful as they are awkward. As

the successive

lights flash they produce movement along the wall and directly affect the

rest of the

environment.

The mechanical operation of a film projector is in itself the ultimate illustration

for the theme of

the show. And Jonathan Monk (b. 1969) is the ultimate artist to make use of

a film projector.

His 16mm installation consists of squares of uniquely cut pieces of black

paper projected

within a thin frame drawn in pencil. These squares have been cut by hand using

a scissor,

preventing the artist from attaining clear-cut corners and straight edges.

The projection on the

wall therefore shows a slightly disturbing and jumping image within the static

pencil frame.

Every fourth frame actually includes a perfectly cut square that fills the

pencil frame, but this

appears too fast to be recognized and you only see it subliminally. Just like

Ceal Floyer,

Monk draws strongly upon the legacy of conceptual art, cleverly combining

homage with

humour and he deals with principal issues of art through his highly referential

work. By

effectively assembling or re-assembling images, puns, objects and ideas, Monk's

art is

always as nifty as it is deadpan funny [2].

We would like to thank all of the artists for their interest in participating

in this exhibition and

providing the work on display, and we would like to thank the respective galleries

of the artists

for their kind assistance and excellent co-operation: Olivier Belot/Galerie

Yvon Lambert,

Burkhard Riemschneider and Christiane Rekade/neugerriemschneider and Schipper

und

Krome. Special thanks to Uwe Schwarzer/Mixed Media Berlin for assisting with

the

production. Finally we would like to thank the family of Michel Majerus.

Ceal Floyer is represented by Lisson Gallery, London and Casey Kaplan, New

York. Sol LeWitt and Jonathan Monk are represented by Galerie Yvon Lambert,

Paris, and Lisson Gallery, London. Michel Majerus and Rirkrit Tiravanija are

represented by neugerriemschneider, Berlin. Liam Gillick is represented by

Schipper und Krome, Berlin; Corvi-Mora, London; Casey Kaplan, New York; Hauser

& Wirth & Presenhuber, Zürich and Air de Paris, Paris.

NOTES:

1. The footage and the recorded sound was edited by following the structure

of a Dead

Kennedys song which has been used as an under laying blueprint when editing

the video. A

four-stroke rhythm is based on beats per minute (bpm). The PAL video system

is based on 25

frames per second (fps). The footage was edited by translating bpm to fps:

1 second is equal

to 25 frames and more or less 120 bpm. 4 frames are then one click in a four-stroke

rhythm.

With a structure of 4, 8, 16, 32, etc. frames, it is possible to edit the

footage by counting the

frames, comparing it to the shape of the sound waves of a given song, in this

case a tune by

the Dead Kennedys.

2. The artist himself states: "If you stare at a blank page for long

enough it starts to move and if

you stare at a printed page for long enough it starts to move (even more)

and caricature or

cartoon or comic book or artist or flip book or artist book or animation cell

or serial repetition or

endless loop and twenty four frames a second or more or less and one hundred

cubes cantz

or Sol LeWitt or Ed Muybridge or still images or sixteen millimetre or post

cards zooming in and

zooming out slowly slow quick quick slow front to back back to front on its

side forever

repeating (almost) the same image equals slight movement and color change

and even "Six

Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object" in only twenty seconds

or forever over and

over or under and above until it vanishes from the screen through wear and

tear and lines and

forms equals only twelve drawings filmed from the front to the back and back

again equaling

one second of time flashing onto the screen breaking up the bright light of

nothing (repeat only

slower and in a deeper voice)..."

(Jonathan Monk, "Sol LeWitt Lines & Forms Yvon Lambert

1989 front to back back to front with blank space ten to one forever",

2000, from the show

"Animations" at PS1, New York, 2001/2002.)